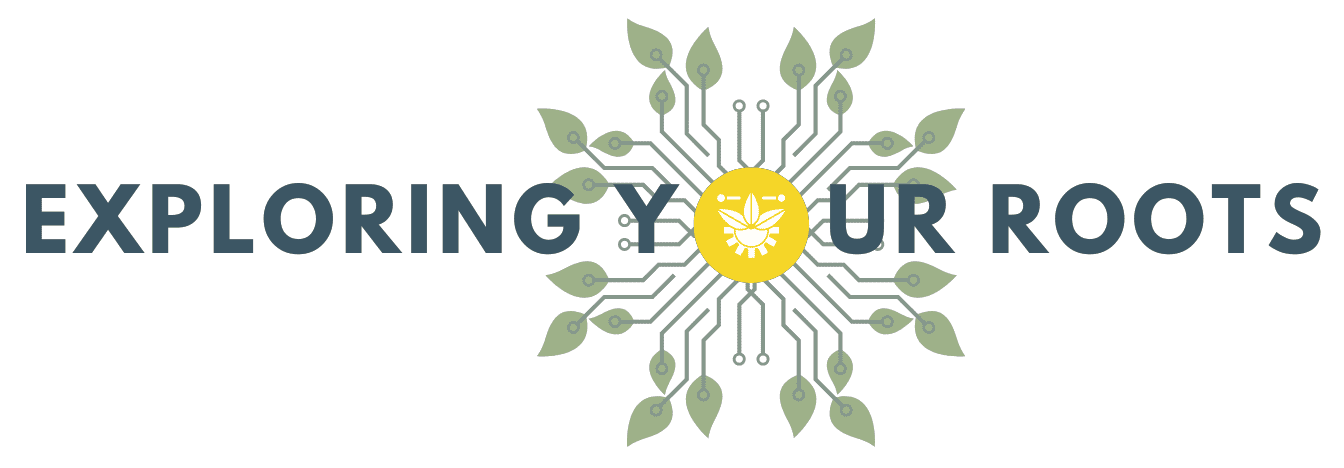

A study of Victorian photos is a captivating voyage through time, where sepia tones and delicate images transport us to an era of corsets, horse-drawn carriages, and whispered secrets. The Victorian Era, spanning from the early 19th century to the dawn of the 20th, was a period of grandeur, societal shifts, and—yes, you guessed it—photography. It’s likely that box of old photos your grandparents or great-grandparents had stashed in the attic contains some Victorian photos.

Imagine gas lamps flickering on cobblestone streets, ladies in voluminous skirts sipping tea, and gentlemen sporting impressive mutton chops. It’s on this enchanting backdrop that photography emerged, like a shy debutante stepping into the limelight. So, tighten your cravat and adjust your bonnet; we’re about to unravel the mysteries of Victorian-era photography.

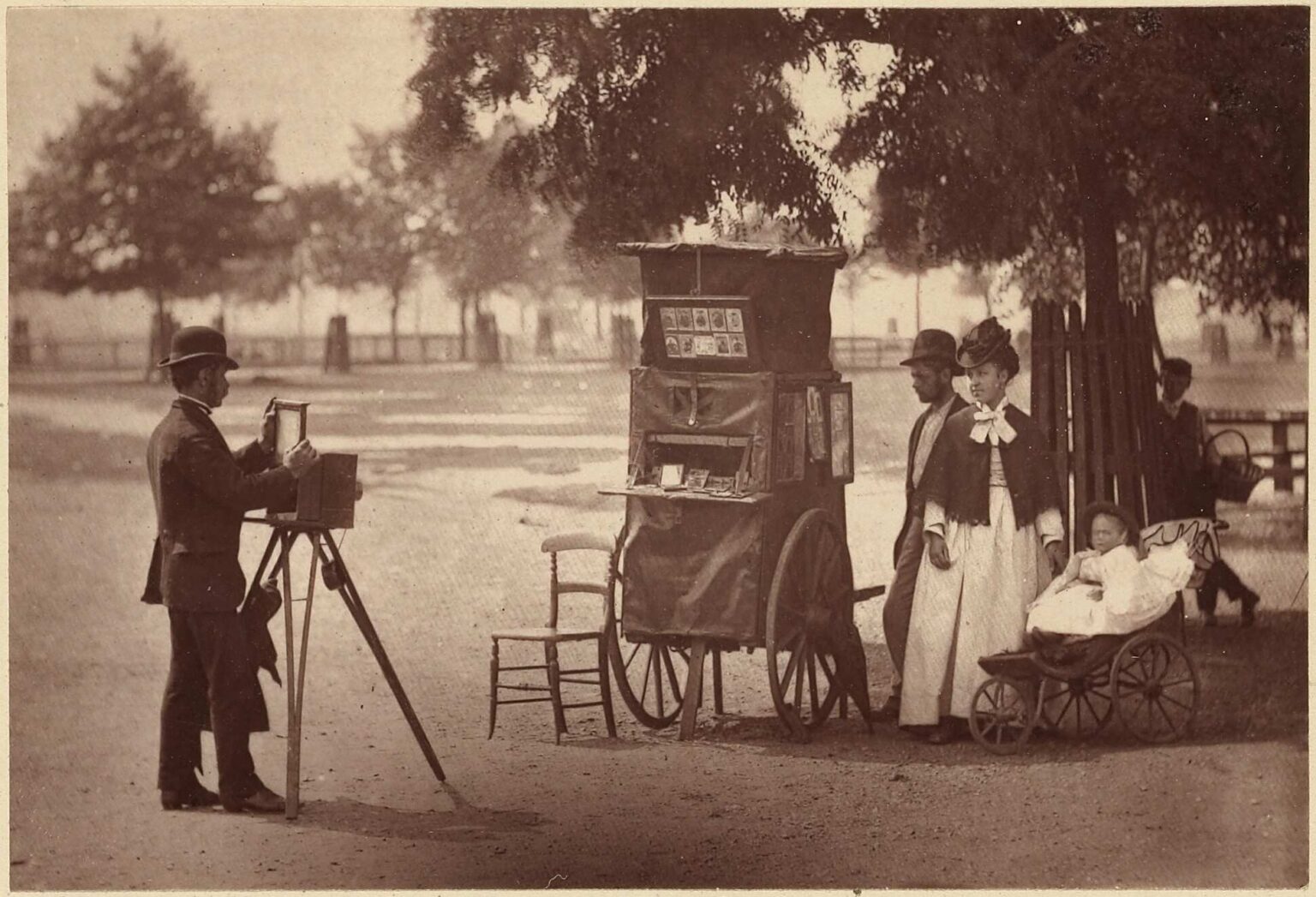

The Daguerreotype: A Mirror of Time

What Is a Daguerreotype?

Picture this: a silver-coated copper plate, meticulously polished to a mirror-like sheen. Enter Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, a Frenchman with a flair for invention. He concocted a magical process that captured light and etched it onto this polished surface. Voilà! The daguerreotype was born.

These early photographs were like delicate whispers from the past. Each one unique, irreplaceable, and as fragile as a butterfly’s wing. Imagine holding history in your hands—the glimmer of a forgotten smile, the twinkle in a lover’s eye, frozen forever.

Daguerreotypomania: The Obsession

In France, daguerreotypes sparked a frenzy. People queued up, clutching their pocket watches and cravats, eager to immortalize their existence. It was the Instagram of its time, minus the avocado toast. Studios sprouted like mushrooms, and soon, everyone wanted their likeness captured. The result? Daguerreotypomania—a delightful word that sounds like a dance move but really means “obsession with shiny silver pictures.”

Reflective Surfaces and Hidden Stories

Hold a daguerreotype to the light, and you’ll see more than just a portrait. You’ll glimpse the room where it was taken—the ornate wallpaper, the chipped teacup on the mantelpiece. These reflective surfaces were like time-traveling mirrors, revealing secrets beyond the subject’s stern expression.

And oh, the stories! The daguerreotype of a dashing gentleman might hide a locket containing a lock of his sweetheart’s hair. Or perhaps a grieving widow clutched her late husband’s image, tears staining the silver. These tiny cases held memories, love, and loss—a microcosm of life itself.

Fragility and Treasured Objects

Handle a daguerreotype with care. It’s not just a photograph; it’s a whisper from the past. These delicate plates were susceptible to scratches, tarnish, and fading. Imagine preserving your memories on a delicate silver leaf, vulnerable to time’s relentless march. No wonder they were often tucked into velvet-lined cases, like precious secrets hidden in a jewelry box.

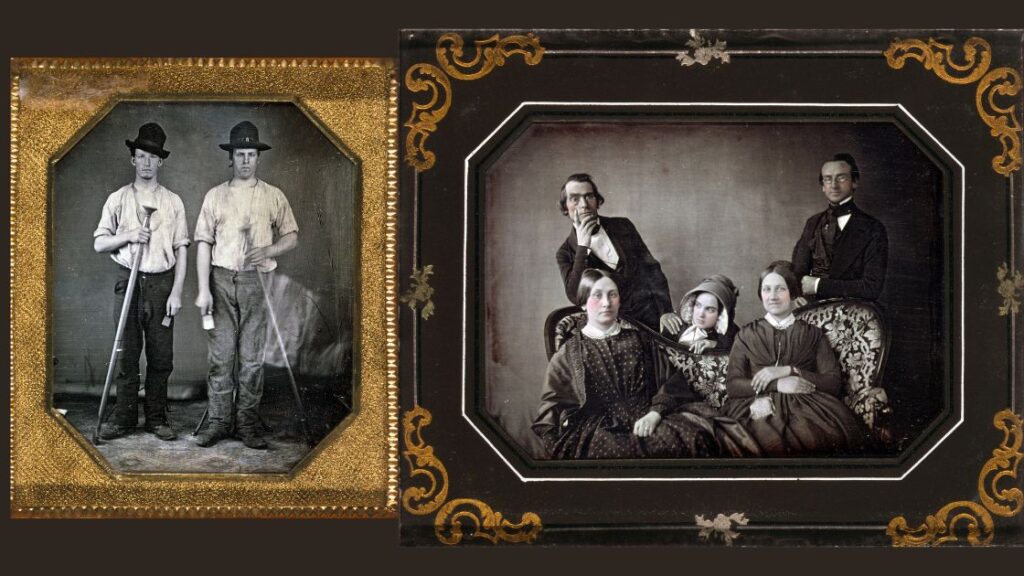

Capturing Stillness: Why No Smiles?

Smiling Was Rare

Next time you flash a grin for a selfie, spare a thought for our Victorian ancestors. They rarely smiled in photographs. Why? Well, blame it on the long exposure times. Picture this: you sit, rigid as a marble statue, while the camera gulps down light for minutes. Try holding a smile for that long without looking like a maniacal tea cozy. Impossible!

Queen Victoria’s Influence

Queen Victoria, the reigning monarch of the time, set the tone. After her beloved Prince Albert’s death, she draped herself in mourning attire—black dresses, veils, and a perpetual frown. The nation followed suit (pun intended). Smiles were reserved for private moments, not for posterity. So, when you see stern-faced Victorians, know that behind those somber expressions lie tales of loss, love, and the weight of corsets.

Beyond the Grave: Postmortem Photography

Hold your breath; we’re entering eerie territory. Victorians had a peculiar fascination with death. Enter postmortem photography—a spine-chilling tradition. Families posed with their dearly departed, capturing a final memory. Imagine Aunt Mildred propped up like a well-dressed mannequin, eyes closed, lips painted, and surrounded by flowers. Creepy? Yes. Poignant? Undoubtedly.

These haunting images weren’t morbid; they were a way to say goodbye. The living and the departed coexisted in sepia harmony. So, next time you scroll through your phone, remember that your great-great-grandparents might have cuddled up with Uncle Edgar’s coffin for a keepsake. It’s like a Victorian version of a selfie, minus the duck face and hashtags.

William Henry Fox Talbot: The Calotype Pioneer

Calotype vs. Daguerreotype

While Daguerre was busy polishing mirrors, across the channel, William Henry Fox Talbot was brewing his own photographic magic. His weapon of choice? The calotype. Unlike the snobbish daguerreotype, which produced one-of-a-kind images, the calotype was democratic. It birthed multiple copies, like a prolific rabbit churning out baby bunnies.

Invisible Latent Image

Talbot’s secret sauce? The latent image. Imagine sprinkling invisible fairy dust on paper, exposing it to light, and—voilà!—images appeared. No mirrors, no silver plates. Just paper, chemistry, and a dash of wizardry. Talbot’s calotype was like the quirky cousin at the photography party—the one who whispered, “Hey, let’s make art accessible to the masses.”

Legacy and Modern Photography

Talbot’s legacy echoes through time. His calotype process laid the foundation for modern photography. Every digital snapshot, every Instagram filter owes a nod to this Victorian trailblazer. So, raise your smartphone (carefully, it’s not a daguerreotype) and toast to William Henry Fox Talbot—the man who turned light into memories.

Conjuring Ghosts: Spirit Photos

Can a photograph provide proof of the afterlife? In the 1800s, photographers like William Mumler and William Hope claimed to be capable of taking photographs of spirits—those elusive beings that straddle the veil between our world and the next. These intrepid souls (pun intended) embarked on a peculiar quest: capturing the ethereal on film.

The Rise of Spirit Photography

After the Civil War, grief hung heavy in the air. Families yearned for a connection with their fallen loved ones. Enter the opportunistic “spirit photographers”—entrepreneurs who promised to summon the departed through the lens of their cameras. It was like Tinder for the supernatural: swipe right, and your late Uncle Edgar might just appear in sepia glory.

William Mumler: The Ghost Whisperer

William Mumler, an American jewelry engraver turned spectral snapper, caused a media frenzy. In 1862, he unveiled a photograph purportedly showing the spirit of his cousin, who had shuffled off this mortal coil a dozen years prior. Suddenly, everyone wanted a piece of the otherworldly action. Mumler set up shop in New York and Boston, offering grieving souls a chance to reunite with their Civil War casualties.

One of Mumler’s most famous images? None other than Mary Todd Lincoln, widow of the assassinated President. There she stood, her eyes fixed on the camera, while the ghostly visage of Honest Abe materialized beside her. Goosebumps, anyone?

The Trick Behind the Treat

But here’s the twist: Mumler’s spectral captures were more sleight of hand than séance. Those apparent spirits? Double exposures of previous clients, lingering on photographic plates that hadn’t been properly cleansed. Oops! Turns out Uncle Edgar was just a lingering photographic residue. The spirit world, it seemed, had a recycling program.

The Decline and Skepticism

Spirit photography boomed until the 1920s, when skeptics like Harry Houdini (yes, the escape artist) decided to debunk the ectoplasmic charade. Houdini, with all the finesse of a magician pulling a rabbit from a hat, exposed the frauds. The jig was up, and the ghostly trend waned.

Victorian Photos Had It All

As we bid adieu to our sepia-soaked adventure, let’s honor the Victorians. They captured life, death, and everything in between. Their photographs weren’t just frozen moments; they were whispers across centuries. So, next time you snap a selfie, remember—you’re part of a continuum. Smile, frown, or strike a mysterious pose; your pixels join the dance of time.

And as the sun sets on our journey, let’s raise our metaphorical daguerreotypes to the past. May our memories be as vivid, our smiles as rare, and our selfies as timeless as those delicate silver plates. 📸✨

Check out the The Evolution of Family Photo Traditions for more interesting tidbits about the history of photography.